Never Let a Good Crisis go to Waste

“…you will ruin fifty thousand families, and that would be my sin! You are a den of vipers and thieves.” — President Andrew Jackson, 1836

In a recent article, Economist Bradford DeLong, shares a conversation he had with U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Janet Yellen, where she said that with the lack of models, the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) is prone to react to the groupthink of media pundits. If true, the Fed, concerned about repeating the mistakes of the 1970s, may be repeating the mistakes of the 1930s. While many suggest Fed chairman Jerome Powell is concerned about being labeled another Arthur Burns (the Fed chair who relented prematurely in the 1970s), he looks like he is repeating the massive policy mistake of Marriner S. Eccles, Fed Chair from 1934 By wrongly assuming the economy had entered a new inflationary era, in 1937 the Fed tightened too aggressively, causing a sharp recession. The result was a return to secular stagnation and deflation.

With the continual unwillingness to acknowledge improving forward-looking data, and with the certainty and bravado of their view to a policy stance, investors need to prepare for the Fed to close their eyes and raise rates to a magical level, say 4.5%, and hope nothing breaks. To wit, the market is positioned for a crash, and investors are incredibly risk-averse. To be clear, we started this year assuming that the Fed would be data-dependent. My assumption was that monetary policy implementation had evolved from being a tool applying blunt force trauma to being an insightful and adaptive tool. I was wrong. For whatever reason, pausing to evaluate after the most extreme monetary tightening in history is a no-go. In 2022, it’s all or nothing for central bankers.

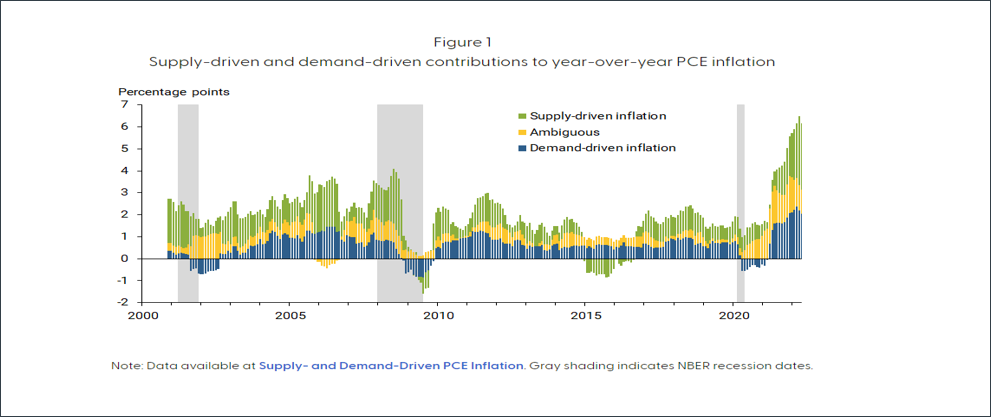

Central bankers have not blinked. Today’s inflation, caused by two exogenous shocks, and pressure from the groupthink crowd coming out of Wall Street, seem to have rattled many global central bankers into their groupthink mentality. We still expect the data to eventually win out, and with the extreme positioning of the market, a short-covering rally cannot be ruled out. But the scar tissue that the Fed has put on capital markets could be generational and may take decades to heal. In capital markets, creditability is a two-way street. To be clear, forward-looking data points to significant deflationary forces in the pipeline. But for investors, with the Fed anchoring off of flawed economic theories, old backward-looking variables, and no working model on inflation, we suggest investors ignore the noise and plan for secular stagnation and a disinflationary environment in 2023. The Fed is poised to make the same mistake it did in 1937.

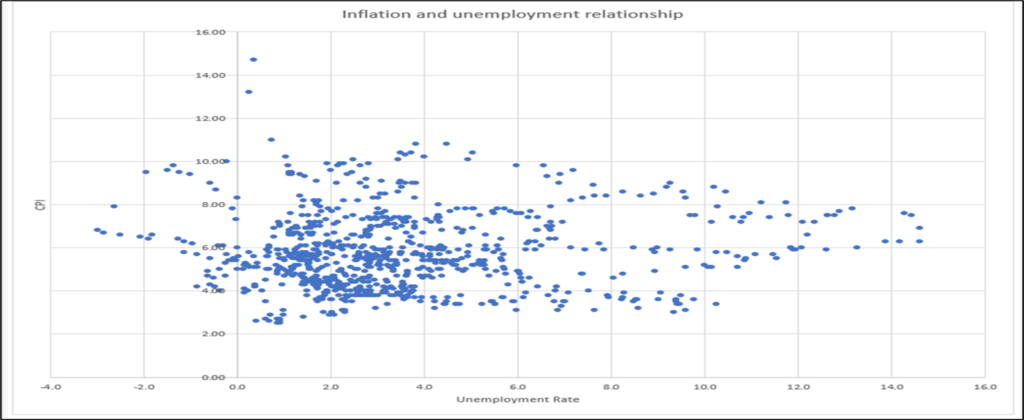

Many have started to voice their concerns over Fed policy, as has been the case in the past. In 1836, U.S. President Andrew Jackson expressed his displeasure with the actions of the Second Bank of the United States. Throughout history, the rise of populism has been the forcing function that has caused a generational change. I believe the rise of populism today does the same to existing institutions and societal norms. After the 2008 financial crisis, with the subsequent election of candidates that shared the views held by President Jackson, one could have easily assumed that policymakers had learned their lesson. They would not inflict pain on the main street to achieve the vital goal of price stability for the economy. All of this changed in the spring of 2022, when in front of the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and G20 Finance Ministers, Chair Powell once again invoked the dubious theory, referred to as the Phillips curve, as the guiding principle to drive monetary policy. To this day, he has not explained the reason behind his pivot.

All of the policy research was, in one fell swoop, tossed in the dustbin. On that day, the Fed pivoted back to the 1970s believing that raising interest rates increased unemployment and brought inflation down. That strategy implies that aggregate demand, specifically wages, is the root cause of inflation. To be clear, given the extreme levels of debt, we are starting to see pushback from many members of society. The central bankers’ response is to close ranks. In a profession where agreement on even the smallest of items is tough to achieve, global central bankers are all in agreement. The unemployment rate must increase, even if wages are not spiralling out of control and real wages are dramatically falling. We hear the circular reasoning — we must have price stability to have a strong job market, and to get price stability, we must make the job market weaker by raising rates.

For some historical context, in 1977, the Federal Reserve Reform Act expanded the Fed’s role to “the goals of maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates.” The goals have come to be known as the Fed’s dual mandate. The dual mandate implicitly assumes a proven stable relationship between inflation and unemployment. History suggests that in times of inflation, the dual mandate turns into a single mandate, getting inflation down. To achieve this goal, getting unemployment up is the misguided playbook used by central bankers. The Act does not spell out the explicit nature of the trade-off between the unemployment rate and the inflation rate, nor does it say how to act if the mandates are at odds with each other. Discretion is left up to the Fed to determine what is more important, inflation or unemployment. The unintended consequence: the Fed does not develop a strategic, holistic view of the complex and essential role in which it operates. The belief was that to defeat inflation, the unemployment rate had to rise. However, every time inflation spikes, the playbook supports raising interest rates to slow the economy and increase unemployment, causing inflation to fall. The Fed is so afraid of making the mistakes of the 1970s – the narrative put forth by the groupthink crowd on Wall Street that it does not realize it’s hovering closer to becoming the Fed of the 1930s.

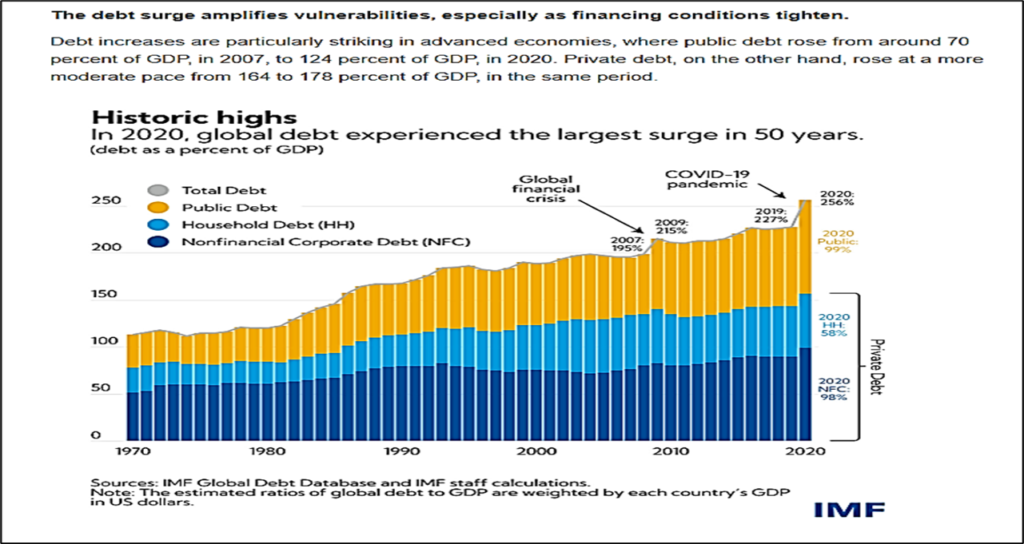

Ignoring this, central banks have embarked on the most aggressive tightening cycle in modern history, into a slowing global economy with a debt-to-GDP of 256%. As a result, the economy is starting to slow, and disinflation is gaining momentum. But the Fed and the Bank of Canada’s desire to anchor off the lagging indicator of the labour market and not anchor off more modern, forward-looking data, increases the probability of a policy mistake. To wit, the data, while being ignored by many central bankers, suggest that mega rate hikes are no longer needed. Recent speeches by policymakers in the U.S. and Canada suggest that this is not on the table. Policymakers will continue flying blind as they aggressively tighten. Many on Wall Street and in ivory towers applaud such bravado, while unfortunately, investors and ordinary citizens who live in the real world feel the brunt of their actions.

We entered 2022 expecting it to be the year of the Fed and for risk assets to have a tough first six months. Forward-looking data points to an ending of the tightening cycle, and investors need to prepare. Unfortunately, the noise that investors need to deal with stems from central banks and their unwillingness to acknowledge the weakening economic environment. The Fed tells us that the economy is strong, while on the other hand, companies are preannouncing, inventories are building, and deflationary pressure is present. Financial stresses are starting to mount and credit spreads are increasing. The recent pension crisis in the United Kingdom and the fast response by the Bank of England should give investors solace that if something does break, central bankers will act swiftly and decisively to ring-fence the market dislocation.

Basic math and the rule of thumb that the Fed will raise short-term rates until they are at least equal to the headline Consumer Price Index (CPI) suggests that by early 2023, rate hikes should stop. Assuming month-over-month CPI comes in at the average of 0.2%, inflation will be close to the Fed’s 2% goal by late spring. If inflation averages 0.1% month-over-month, then by late spring, CPI will be below the 2% target. Using the 1994-95 episode as my guide, we should expect the Fed to alter its tightening strategy in the coming months. In 1994, a mid-term election year as 2022 is, the Fed went on an extreme tightening cycle only surpassed by this year. Once the market processed enough data to feel confident that the Fed was going to downshift the rate hike cycle, risk assets started to appreciate. While we advocate ignoring the noise coming out of the Fed, we still believe they will eventually act rationally and stop the mega rate hikes. To be clear, investors must realize that the Fed’s own research concludes that 2/3 of the current inflation is being caused by factors that are not directly affected by raises in interest rates. The result, the Fed will tighten too much as they always do. Yes, another policy mistake. Unfortunately, one could easily make the argument the Fed does not review its own research before making policy decisions.

To be clear, Chair Powell has shown the ability and willingness to act decisively in the face of a financial crisis. My base case is that he will rise to the occasion again, if necessary. With the extreme negative positioning in the markets, we suggest investors start to position themselves for the rebirth that will take place in 2023. Any indication of the Fed acknowledging the existing financial stress in the system or a downshift in rate hikes will be met with an extreme short-covering rally. As for rate cuts in 2023, no one knows how the economy will evolve; but given the war in Europe and the recent action of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC)+ to side with Russia, investors need to position their portfolios for the coming energy renaissance in North America.

What Should Investors Do?

“In the history of America, we’ve never had an energy plan. We don’t realize the resources available to us.” — T. Boone Pickens

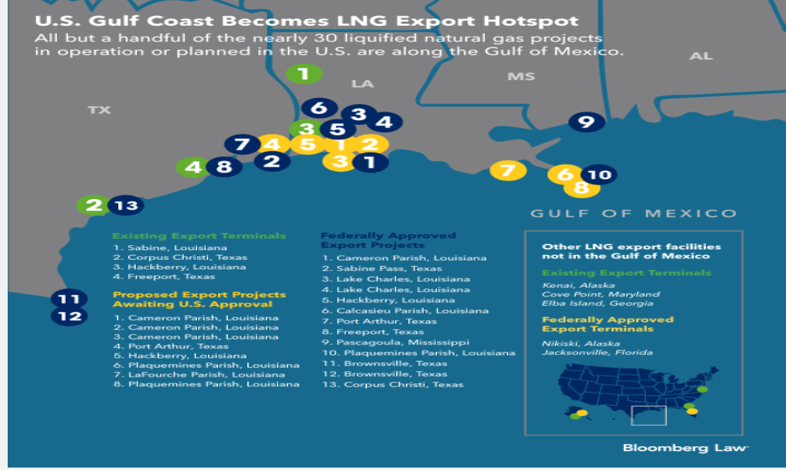

With the war in Europe and the recent actions of OPEC+, we suggest investors prepare for a new era. An era where North America finally develops an energy plan. Forward-looking data points to a more reasonable Fed in the not-so-far-off future when they will pause. Listening to company calls and looking at current real-time data leads us to this conclusion. The positioning in capital markets is extremely risk-averse. There is a higher probability of a melt-up than of a market crash. Thus, an investor should start preparing for a period where capital markets focus on earnings growth and valuation. With the recent action by OPEC+ turning its back on the west, investors need to reconsider their weighting in energy seriously. We suggest a plan as J.P. Morgan’s Jamie Dimon expounded in his yearly letter to shareholders, saying that it should be the base case for investors. The actions of OPEC+ could mean that energy becomes a growth industry again and as Mr. Dimon rightly points out, we need a common-sense plan to transition our economy to our net zero goal. That plan depends on energy security. Mr. Dimon refers to it as an energy Marshall Plan for Europe and North America. Since 1990, the energy sector’s average weighting in the S&P 500 is 8.6% and it typically peaks at approximately 16%. Its weight today is close to 5%. As with every cycle, investors should consider that the energy sector may revisit its peak weighting by the decade’s end.

As Mr. Dimon stated in his letter: “First, we must promote energy security. Constraining the flow of capital needed to produce and move fuels, especially as the war in Ukraine rages on, is a bad idea. The world still needs oil and natural gas today, but not all hydrocarbons are equal when it comes to their carbon footprint. We should be directing more capital toward less carbon-intensive fuel sources and investing in innovations, such as carbon capture and sequestration, as we look to transition to green technologies delivered at scale for society.”

Written before the recent move by OPEC+, the issue of energy security is now front and center, making the need for an energy Marshall Plan even more prescient.

According to FactSet, the energy sector is expected to report the highest (year-over-year) earnings growth of all 11 sectors in the S&P 500 at 117.6%. At the sub-industry level, all five sub-industries in the industry are expected to report a year-over-year increase in earnings of more than 20%: oil & gas refining & marketing (259%); oil & gas exploration & production (121%); integrated oil & gas (103%); oil & gas equipment & services (72%); and oil & gas storage & transportation (22%). The energy sector is forecasted to be the most significant contributor to earnings growth for the S&P 500 for the third quarter.

According to Bloomberg, S&P 500 earnings estimates in 2023 are approximately $240, with $67 of earnings contribution coming from energy – that’s close to a 28% earnings contribution from a sector that has a 5% weighting. This discrepancy between earnings contribution and index weight will be reduced throughout the rest of the cycle. If the energy sector is excluded, the S&P 500 would report a decline in earnings of 4.0% rather than a growth of 2.4%. According to Yardeni Research, S&P 500 energy sector operating earnings per share are at levels not seen since 2007, the peak of the last cycle. What is different today is that energy companies are high-tech, achieving peak production rates with fewer people, resulting in higher margins.

The long-term ramifications of the recent OPEC+ decision to cut output and the war in Europe have yet to be fully felt in terms of geopolitics, economic growth, and earnings growth. The North American energy industry is on the cusp of a new renaissance. Under the radar, liquefied natural gas (LNG) plants are being built in the Gulf of Mexico. The U.S. is now the largest export of LNG in the world. The new LNG plants will solidify their position for many years to come. Investors should follow the earnings growth. For those who do, a significant holding in energy, energy infrastructure, and renewable energies is a simple conclusion. Use the noise created by the Fed to add high-quality energy names positioned for the future. Finally, with the market set for a Fed policy mistake, any hint that objective decision-making has penetrated the groupthink in the Fed could ignite an intense short-covering rally into the end of the year.

— James E. Thorne, Ph.D.

[1] When the Fed Stops Trying. J. Bradford DeLong, Project Syndicate, September 30, 2022.

[2] Jamie Dimon, Letter to Shareholders, April 19, 2022.

[3] Bespoke Research.

[4] FactSet earnings Insights, October 7, 2022.

[5] Yardeni Research, S&P 500 Industry Briefing: Energy. October 7, 2022.

.