“So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

– F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby

Depicting a period of dramatic social, technological and economic change, The Great Gatsby, set in 1922, is often seen as a somber critique of the American Dream. Jay Gatsby overcomes a poor past to gain incredible wealth through bootlegging, only to be rejected by the old money establishment. Gatsby personifies the “lost generation,” manifested from a rise in populism, fascism and communism of the previous decade, in an era in which the loss of hope drove societies to question social norms and prompted generational structural changes.

Today, we find ourselves at a similar crossroads. The Covid-19 pandemic has amplified a rise in populism. With digitization and the greening of the global economy, as well as the desire of central bankers to target capital creation to stimulate economies and reduce income disparity, we have entered into a period of extreme change similar to the 1920s. Our base case suggests that a new business cycle has begun, with interest rates at generational lows and tempered long-term inflation expectations. As central bankers focus on reducing income inequality, this will usher in structural change that may bring a prolonged period in which risk assets appreciate. To wit, the 2020s could shape up to mirror the Roaring 1920s and investors should be prepared.

The Roaring 1920s: A Bleak Beginning

The backdrop for the Roaring 1920s was a culmination of many events. Germany unified in the late 1800s, and by the 1900s was taking market share from other European economies. At the same time, the U.S. was laying the foundation to become a global economic power.

To be clear, the beginning of the decade was bleak. In 1920 and 1921, an economic slump afflicted the U.S. – a depression that history has forgotten. Real output fell by 9% and unemployment soared as high as 19%. Its roots lay in the preceding boom. When World War I (WWI) broke out in 1914, skittish European investors began shipping their gold to the U.S. The influx swelled the money supply, leading to an explosion of spending, credit and prices. European demand for U.S.-made products significantly increased and prices doubled between 1914 and 1920. In response, Benjamin Strong, head of the New York Federal Reserve Bank, began to raise interest rates. Industrial production contracted, prices started to plunge and populism took root. The monetary squeeze was severe: interest rates surpassed 15%; fiscal policy was equally austere. Then, as the world emerged from WWI, it was shaken by the Spanish Flu pandemic which killed an estimated 20 to 50 million people. Fascism and communism continued to take hold in Europe.

Central Bank Intervention in the 1920s

In an attempt to temper the rising unrest stemming from the depression and improve the economic situation, Benjamin Strong took unprecedented and aggressive action. For the first time, open market operations would be used through a large purchase of government securities to significantly increase the availability of credit in the banking system. Strong postulated that if a shortage of credit was causing an economic decline, why not find a way of increasing reserves to the banks such that the economy would never be short of credit. Thus, if banks could continue to loan money indefinitely, the extreme swings of the business cycle would be reduced. While the U.S. remained on the gold standard, in addition to gold, credit now extended by the Federal Reserve banks could also serve as legal tender. This helped to create one of the strongest innovative and economic growth decades of the 20th century.

Technological Transformation

Supported by the influx of available credit, technology would fundamentally alter the structure of the economy. The driving force? Electricity. In 1907, only 8% of households had electricity; by 1930, this reached over 68%. Improvements in the availability of central heating and indoor plumbing facilitated new technologies – washers, electric irons, refrigerators and more. This raised living standards, created new jobs and gave rise to a new middle class, and the American Dream.

By 1929, more than 70% of industry was powered by electricity. The iconic symbol of this productivity boom – the Model T Ford – rolled off the assembly line every 10 seconds. Before WWI, a Ford cost the equivalent of two years’ wages for the average worker. By the late 1920s, it was only around three months’ earnings. Increased productivity led to the mass production of many consumer products and the rising tide lifted all boats.

Technological Transformation 2.0

In 2003, Jeff Bezos delivered a TED talk that used the 1920s electricity swell as a metaphor to describe the future impact of the internet. While the internet bubble had popped years before, he suggested that future web-based innovations would significantly transform society, just as electricity improved household productivity in the 1920s by liberating women from work in the home. This increased the time available for leisure, education and eventually work in the market sector, shifting society from a rural to urban economy. Fast forward to today, and we see the introduction of electric cars, social media, new transportation platforms and innovative healthcare techniques, to name a few, emerging in this new digital landscape. With 65% of the world economy yet to digitize, the transformation is far from over.

The Roaring 2020s?

Beyond this technological transformation, where we find ourselves today has similarities to the past. In the 1980s, East and West Germany were reunified and China began to open its economy, laying the foundation for this generation’s globalization. Decades later, both economies would capture manufacturing market share and export deflationary forces to the world. While central bankers pacified inflation by subduing wage growth, the seeds of populism were being sown.

Central Bank Intervention Today

The effect of the pivot by central bankers will likely be most profound. Over recent years, they have fessed up to their part in the rise of populism. The previous Paul Volker playbook focused on wage inflation in an era in which the major economies of Germany and China injected massive overcapacity into the global economy while the deflationary forces of technology were unleashed. Inflation may have been controlled below the magical 2% level, but at what cost? The hollowing out of middle class manufacturing jobs gave rise to the massive income inequality we see today and a significant portion of the population feeling as though hope is lost.

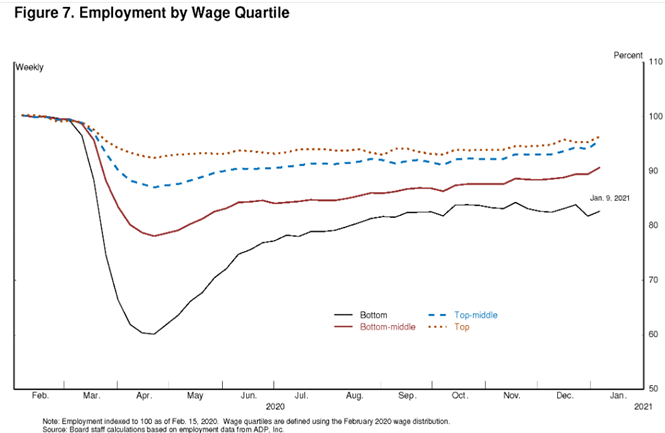

Today, Fed Chairman Powell has made this generational pivot. His recent speech on the labour markets explicitly focused on the extreme unemployment levels of low-income families and the disproportionate cost of the Covid-19 pandemic on this group. He reiterated that the previous focus on the relationship between wage growth and inflation was a mistake.

Figure: Employment by Wage Quartile

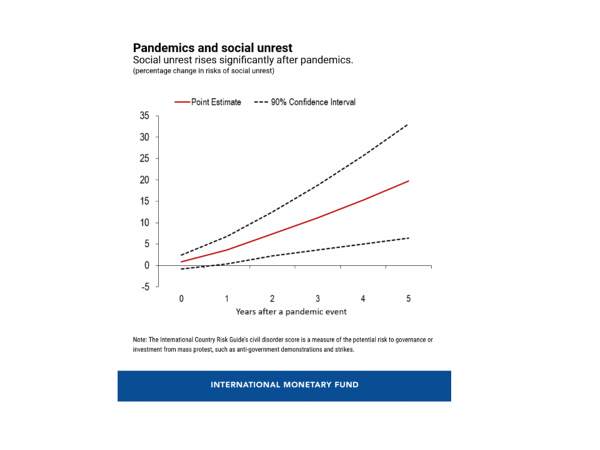

Simply put, Powell suggests that, like Strong did in the 1920s, he will keep monetary conditions extremely loose for some time. As we look forward to a post-pandemic economy, income inequality will not simply vanish if we reach herd immunity. Pandemics amplify the forces that create income inequality and can linger for years – and Powell has pledged to continue to temper these forces.

Graph: Social Unrest Rises Significantly After Pandemics

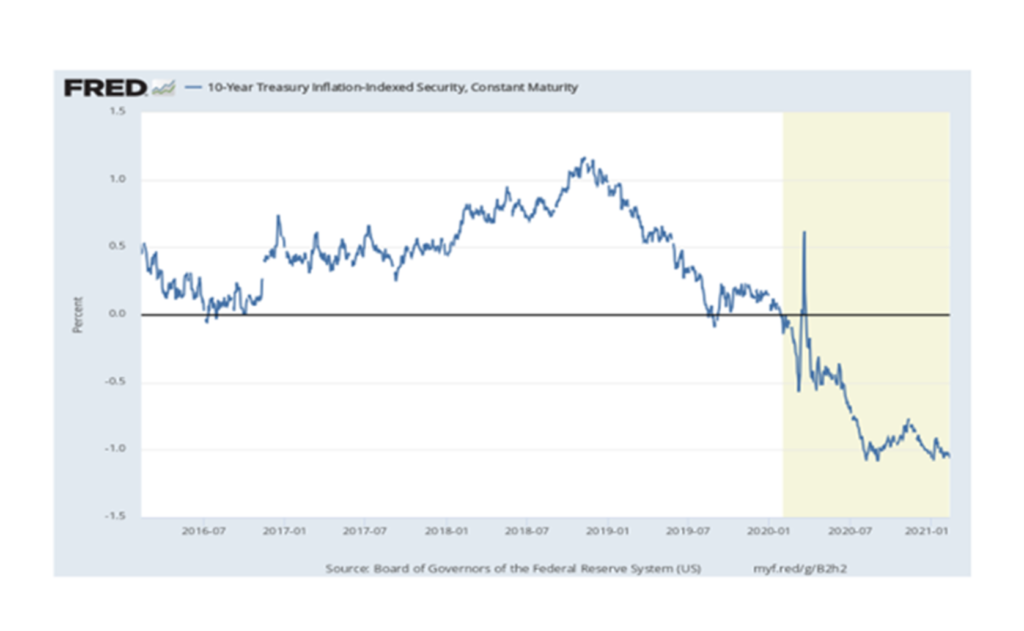

What does this mean for investors? The old investing playbook needs to adjust. With decades of capital flows continuing into bonds, investors need to be prepared for a reversal. How much longer will investors buy bonds with yields at generational lows? With the yield on the 10-year TIPS at -1%, suggesting that investors are willing to pay the government 1% for the right to own a 10-year government bond, the old saying goes that both markets and investors can act irrationally for some time.

Graph: 10-Year Treasury Inflation-Indexed Security (TIPS)

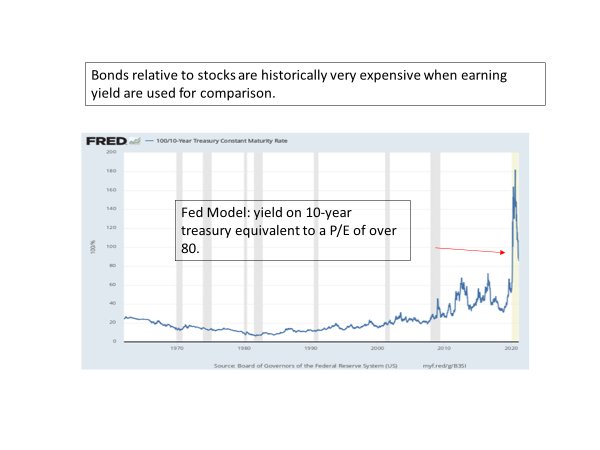

A simple model used as a guide for interpreting the relative value of stocks to bonds, known as the Fed model, compares the earnings yield (E/P) of the S&P 500 to the yield of the 10-year Treasury bond. Using the closing yield of the 10-year Treasury at month end, the equivalent price earnings ratio would be over 80! This indicates that equities are undervalued.

Graph: Fed Model – Bonds Expensive Relative to Stocks

Looking forward, today’s Gatsbys – the Millennials and GenXers – will shape social norms and determine what is acceptable, including investment preferences. Financial markets aren’t immune to these changes: the green economy, sustainable investing, stakeholder value, passive investing, options, digital assets, digital platforms and the questioning of past generational norms will only intensify.

In 2021, we find ourselves at the start of a new business cycle that may last up to eight years: bonds are expensive relative to stocks, the Fed will continue to be accommodative by anchoring interest rates, and, as the economy opens, expect a cyclical recovery with inflation slowly increasing (but not accelerating to extreme levels that many are predicting). Earnings will be strong, with a year-end target of 4,500 for the S&P 500.

With a new era upon us, we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past. Fitzgerald was right. Let the Roaring 2020s begin.